What is adultism?

Adultism is discrimination against young people because of their age. It is probably the most widespread form of discrimination worldwide, and it is based on the assumption that children and adolescents have less to say, that they are less intelligent, or less valuable. If you take a closer look, you can see that this assumption is deeply embedded in society and affects many areas of life.

In urban planning, children are often barely taken into account – for example when streets are designed primarily for cars rather than for children’s safe and independent mobility. Sometimes this also shows up in very simple things, such as supermarket doors that do not open if you are below a certain height, or in other everyday practicalities in which children are not considered (and which go beyond a purely protective function). This naturally restricts young people’s independence, as there are many things they cannot do unless an adult accompanies them. It also limits their opportunities for learning.

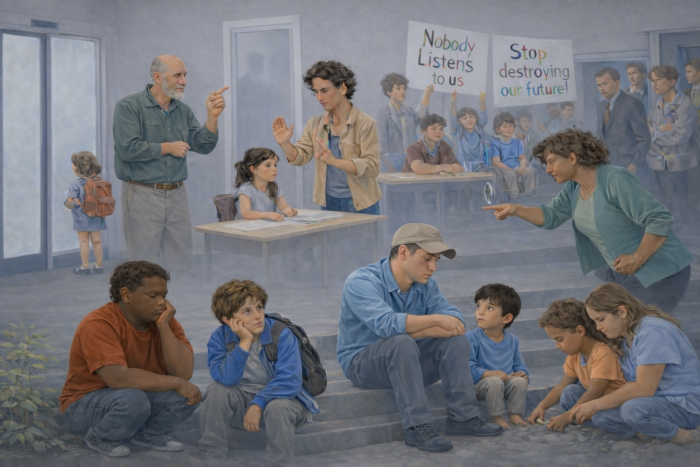

At the political level, children and young people are often talked about, but almost never talked with. Due to existing voting rights and political structures, their voices are largely ignored. Their opinions carry little weight, and when they attempt to make themselves heard through other means – such as the Fridays for Future movement – they are often dismissed as immature, unrealistic, or motivated purely by selfish interests (for example, the familiar accusation of “skipping school”).

Adultism is also reflected in the language we use. How do we talk about young people, and how do we talk with them? A useful exercise is to notice phrases you might say to children without much thought – or that you hear others say – and ask yourself whether you would say the same thing to a friend or partner. A common example is: “Don’t make such a fuss.” This denies young people the validity – or even the reality – of their feelings or pain. Imagining saying this to an adult during a difficult moment quickly reveals how disrespectful such an interaction would be.

What are the effects of adultism being prevalent in society?

Adultism can have a strong impact on young people’s self-esteem. If we tune into our own experiences, it often becomes clear that decades later we are still influenced by how we were treated in childhood. I see the widespread popularity of working with the inner child or inner parts as a clear indication of this.

An adultist, condescending attitude towards children and adolescents often leads to lower self-esteem and to the assumption that one cannot rely on oneself. This can involve losing trust in one’s own perceptions or abilities. When you believe that you do not know enough or cannot do things well, you tend to orient yourself strongly towards the outside. Over time, this makes it increasingly difficult for many young people to stay connected to themselves and to know: What do I enjoy? What am I good at? What do I need? Who am I, really? Through repeated interactions shaped by adultist attitudes, they may learn to hold themselves back more and more.

Adultist behaviour can also generate fear. Although physical violence against children has fortunately declined significantly over recent decades, violence still appears on other levels: psychological, emotional, and spiritual.

What structures, value systems, and assumptions is adultism based on?

At its core lies the – conscious or unconscious – assumption that children are less intelligent and therefore always need older people to instruct them. Of course, children are not small adults; they are at a very different developmental stage, and it is important that adults are there for them. However, the assumption that children always need instructions about what to do, how to handle things, or what the next “right” step is, is highly problematic.

This adultist attitude is also reflected in the concept of upbringing, which reproduces an asymmetrical power relationship and leaves little room for exchange on equal terms. On one side stands the parent or educator; on the other, the young person – more like a one-way street than a dialogue. I still see a great deal of authoritarian structure here, and perhaps even – often unconscious – fantasies of power.

Language, too, reveals a broader societal attitude. When talking about a child, people sometimes refer to them as “it” rather than “he” or “she”, which reflects a form of objectification.

How can this adultist way of relating to young people affect their later life paths, working lives, and social participation?

The constant presence of external evaluation and fear – whether explicit or subtle – certainly inhibits initiative. On the one hand, this can function as self-protection against negative judgement; on the other, over time, it becomes a habit. If, whenever you want to do something you feel drawn to, you are held back – at home, at school, or in after-school activities – because something else is considered more important, it is hardly surprising that intrinsic motivation eventually fades. In its place, waiting for external instructions can become the norm. Openness towards other people can also be persistently and negatively affected by adultism.

Beyond this, we are also confronted with the question of how success is defined: What is at its center? For young people, success is almost inevitably framed in terms of getting good grades, being “well-behaved”, and being praised — or at least not criticised. Their attention is constantly directed towards the future through phrases such as: “You’re not learning for school; you’re learning for life” – where “life” almost always means life in the future. You have to do this now so that you can get a good qualification, so that you can study, so that you can get a good job and earn a lot of money. Then you’ll be successful.

But success could be defined very differently. Are you happy? Are you doing something you enjoy? What is your social and ecological impact? I believe that young people often have a very clear sense of this intuitively, but that it is gradually unlearned over time through exposure to adultist behaviour and the internalisation of capitalist norms and expectations.

Another important aspect is that authoritarian structures are, by their very nature, anti-democratic. It is paradoxical and counterproductive to encourage young people to participate in society while, in practice, their opinions usually carry very little weight. One can speak endlessly about the importance of democracy and the need to protect it, but as long as children and adolescents cannot experience it in real life – with real consequences, rather than only in theoretical scenarios or simulations – this remains largely meaningless.

What is needed are genuine horizontal structures and a culture of open exchange and discussion, independent of age. Only then can young people grow into democratic or sociocratic processes with confidence. As a prerequisite, it must be acceptable to think in different directions and to question things; there must not be a single “correct” answer or opinion imposed from the outside.

What can we do to counteract adultism?

I believe the most important starting point is to engage with our own attitudes and to question what we say and do. This means developing an awareness of how we relate to young people, and why. What lies beneath our behaviour?

Much of what we do happens more or less automatically, because we have internalised many of our own childhood experiences and often pass them on in a relatively unfiltered way. From my own experience, I know that even when someone has done a great deal of personal development and inner work, they can still be strongly triggered as a parent – or when working professionally with children. This is because so much unconscious and unresolved material may still be present.

This is where we need to look closely and ask ourselves questions such as: What am I actually saying right now, and why? Is this really what I want to model? Is this how I want to influence this young person’s development? In this way, we can help prevent these patterns from being passed on to the next generation.

On a practical level, it is incredibly important to create spaces for free play and creativity. Many young people today have extremely overloaded schedules filled with learning and leisure activities. Much of this can be valuable in itself, such as music lessons or sports. However, young people urgently need spaces where they can experiment and explore, ideally with people of different ages – and, crucially, without instructions and without evaluation.

Adventure playgrounds are a beautiful example, offering building materials and tools for free use. In such places, it quickly becomes apparent how capable children and adolescents are of working as a team when they are simply allowed to get on with things. It also becomes clear how well they can plan, how much intrinsic motivation they have, and how much genuinely hard work they are willing to do when they share a common goal. Free play and creative making are also democratic processes. A great deal has to be negotiated: How do we want to start? Who does what? That didn’t work – how could we do it differently?

In spaces like these – which may look very different but are based on the same core principles – young people can experience themselves as effective agents and as valuable members of a community. It is especially important that these spaces are free from judgement, because genuine experimentation is impossible under constant evaluation.

At a deeper level, what we need is a different culture around mistakes. Making a mistake is not something bad in itself; it is a learning experience. We all learn best when we are allowed to make mistakes without being punished for them. Under such conditions, different ways of being together across age groups can begin to take shape – including more constructive ways of dealing with conflict and allowing human potential to unfold.

This text is based on a video interview with Nina Downer, conducted by Nadjeschda Taranczewski, that was transcribed, translated from German, and partially rewritten.