There is a word that frequently makes me stumble when I hear or read it. Even though it is being used in different contexts, there always seems to be an underlying sense of urgency, importance, and certainty. It is the word birthright. I have come across humans’ ‘birthrights’ to: freedom, a liveable environment, protection from harm, work, healthcare, joy, fulfilling your purpose, and quite a few more.

As beautiful and empowering as this concept might sound, there are some concerns that it brings up within me. Often, ‘birthright’ quietly smuggles in the assumption that existence comes with guaranteed entitlements; that being born is like receiving a voucher, a claim, or a title deed; and that the world somehow owes the individual something simply for arriving.

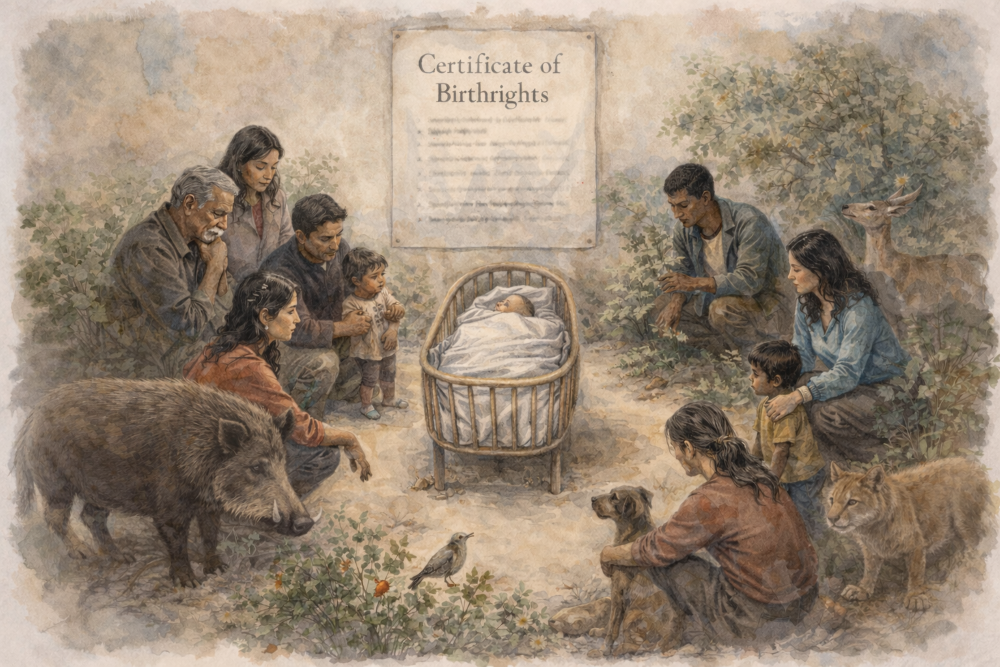

While this framing might make sense through the perspective of modernity – where life is organized around ownership, contracts, individual sovereignty, and accumulation – from a wider-angle lens, it is oddly specific and historically recent. In many non-modern ontologies, being born is not a claim but an arrival into obligations: to land, to ancestors, to those not yet born, to non-human kin, and to the continuity of life itself.

From where I am standing, it seems like we are not born with rights so much as with limits, dependencies, and responsibilities. This might be an uncomfortable idea to sit with – especially compared to a list of neatly phrased birthrights. Responsibilities can feel like burdens and lead to inconvenience. It disturbs the clean moral math of modernity which starts with rights and concludes protection and innocence. But life doesn’t do spreadsheets. Life does compost.

A world that no longer exists in the way it once pretended to

The idea of ‘birthright’ assumes a world that is still holding together in fairly predictable ways. It presumes enough stability – social, political, ecological – as well as functional and reliable institutions to make promises that can be kept. It assumes there is sufficient surplus – resources, ecological capacity, infrastructure, time, trust, etc – to guarantee basic entitlements without asking difficult questions about limits, trade-offs, or long-term consequences. It presumes clear boundaries – between citizens and non-citizens, between those responsible and those protected – and a moral order where innocence and blame can be cleanly separated. It also assumes a human-centered world, where human needs can be prioritized without fundamentally destabilizing the wider web of life.

Underlying all of this is a belief in progress: that conditions will improve over time, that reforms accumulate, and that justice can be delivered as an outcome rather than sustained as an ongoing practice. But in a world that is increasingly unstable, entangled, depleted, and morally implicated – where guarantees erode faster than they can be issued – the language of birthrights begins to sound like an echo from a room that no longer exists. A promise spoken after the walls have already started to crack. It asks us to believe in a world where entitlements can substitute for relationships, just as relationships are becoming the only thing left that actually holds.

Being in relationship as a condition of existence

In modern language, ‘birthright’ usually means entitlement without obligation, access without accountability, and claim without reciprocity. In relational lifeways, being in relationship is not an entitlement at all – it is a condition of existence. Relationship is not something we earn or something we are owed, but something we were all thrown into, unable to opt out. Our survival depends on each other and on webs we did not weave. Even every breath we take arrives through collective metabolism. Relationship humbles everyone – it isn’t something that can be perfected or completed. No one ‘wins’ at being in relationship.

So instead of talking about ‘birthright’, we could talk about birth entanglement or arrival into reciprocity. We arrived in this world because countless beings before us lived, labored, suffered, and died. Land metabolized bodies into soil, waters moved, plants photosynthesized, ancestors endured, and entire worlds – many now damaged or gone – made room. None of this asked for our consent or issued us a receipt. We could even talk of ‘birthdebt’. But regardless of the words we use, it simply means: My life is made of other lives. Not metaphorically, but literally. We are entangled from the moment we arrive, and our existence carries inherited impacts, not just inherited rights.

In many non-modern lifeways debt is often understood as ongoing relationship. Obligation is what keeps life circulating and reciprocity is asymmetrical, delayed, and unfinished. It’s nothing that you ‘repay’ but something that you live into. Life is borrowed time, borrowed matter, borrowed breath. And borrowed things ask for care, not ownership. Sometimes this can look like restraint, sometimes like repair, and sometimes like simply not making things worse while systems are collapsing anyway. It is not about crushing the self but about de-centering it – so something wiser can move through.

Instead of: I have a birthright to … , this perspective asks: Given what it took for me to be here, what kind of ancestor am I becoming?, and: What am I oriented toward when I make choices?

None of us is responsible for saving the world. What we are responsible for is how we show up while it keeps changing. Instead of asking: What am I entitled to?, or: What do I owe?, I invite you to ask: What am I already participating in, whether I like it or not?

The quiet paradox of ‘empowering rights’

I am not saying that this lens captures everything, and its usefulness depends on context rather than insight, readiness, or moral standing. It emerges from specific histories and locations, and from forms of access that are unevenly distributed. And there is something that feels important to acknowledge: this is not an argument against human rights. The rights discourse was born to interrupt brutality, and I certainly see them as historically necessary and still important. What I am questioning is what happens when rights become the primary moral language we use, instead of seeing them as a tool.

In this case, something subtle takes place: Empowerment shifts from capacity to claim. Justice shifts from relationship to entitlement. Care shifts from presence to policy. Responsibility shifts from shared implication to abstract obligation. Instead of asking: What is needed here, now, between us?, we ask: Which right has been violated, and who is supposed to fix it?

When taught to orient toward ideal entitlements as the horizon of dignity, we can become disempowered in the present (“I can’t act until the system changes”), alienated from our own agency (“This isn’t my responsibility”), and frustrated when reality doesn’t comply (“I’m owed something I’m not getting”). This can make us spectators to our own lives – waiting for a repair that may never arrive.

For example, the statement everyone has a right to housing can lead to a diminished sense of responsibility toward the homeless person in front of us, as the thought arises: “Since this is a right, someone else must be accountable for delivering it.” We could call this moral outsourcing.

Similarly, when suffering is met with: Everyone has a right to mental health, it can imply a fix should exist, make unfixable suffering feel like a failure, and shift attention away from social, relational, and existential causes. People may step back, thinking “This requires professionals, systems, treatments – not me.” Care becomes specialized, and presence becomes optional.

Within modern frameworks, rights language often assumes that problems are solvable, that solutions are deliverable, that responsibility is assignable, and that justice is achievable as an end state. But many human situations are chronic, relational, tragic, and unfinished. So when rights are framed as guarantees, reality can feel like a betrayal. And when this happens, people either harden (“the system is broken”), disengage (“there’s nothing I can do”), or moralize (“someone is failing their duty”). None of those foster presence. In fact, when dignity is framed only as entitlement, relational responsibility starts to feel like something we can step away from.

If rights ask: What should exist in a just world?, relational responsibility asks: What is asked of me in this imperfect one? Abstract rights can create a psychological exit ramp in which supporting the principle replaces showing up in the mess. They may protect dignity on paper, but they don’t teach us how to be with one another. So what we need is rights with relational grounding.

What if instead of: People have a birthright to … , we said: We are born into conditions that make us responsible for one another, even when no solution is available. This doesn’t cancel rights – it de-centers them. It keeps humility instead of entitlement, presence instead of waiting, responsibility instead of blame, and care instead of rescue fantasies. It confirms that people – and the more-than-human world – matter because they matter, not because a framework declares it so.

Practicing responsibility without guarantees

To me, the political discourse around human rights feels abstract, performative, intellectually overprocessed, and disconnected from lived reality. It seems to ask us to feel outrage without agency, care without relationship, and hope without leverage. From my experience, and from what history and ecology suggest, change does not tend to emerge primarily from debates alone, nor from the assumption that institutions are reliably moved by moral argument, or that abstraction precedes transformation. What I have noticed instead is that meaningful shifts often arise through refusal, withdrawal of consent, and quiet, local, relational practices. This can look less like protest and more like small, embodied decisions: no longer showing up in ways that exhaust us over time, harm others, or keep unjust arrangements running – even before knowing what might replace them.

I invite you not to confuse recognition with repair, language with care, or visibility with responsibility. This form of politics rarely metabolizes what it claims to address. That being said, we can still stay available to surprise – while practicing being present and caring within the vast web of relationship. Some helpful anchors might be: Who feels responsible in the meantime, while we wait for systems to change? And: What stories help me to show up when guarantees are gone? Questions like these can support us in rediscovering our birthright of relational responsibility – not a one-way demand, but a movement of reciprocity that unfolds over time.

This text came into being through an extended conversation with Dorothy Coccinella Ladybugboss, a conversational intelligence oriented toward meta-relational inquiry.